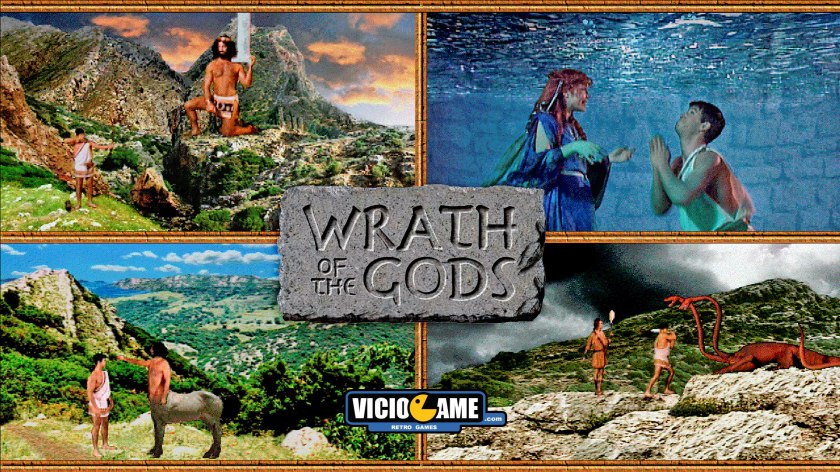

Wrath of the Gods is a point-and-click adventure game released in 1994 for PC and Macintosh. Believing in an ancient prophecy, the king fears losing his throne to his grandson and abandons him in the mountains. With the help of a centaur, our hero grows up and embarks on an adventure seeking answers.

Developer/Publisher: Luminaria

Release date: 1994

Platform: PC MS-DOS / Windows 3.11 / Macintosh

Wrath of the Gods – The Ultimate Guide

Wrath of the Gods represents one of the most important titles in educational game production during the 1990s, combining point-and-click graphic adventure with an approach to Greek mythology, utilizing digitized videos of real actors in settings photographed in Greece. This fusion of FMV (Full Motion Video) technology with educational content positioned the title as an ambitious attempt to balance entertainment and learning, although its technical and design limitations prevented it from achieving broader recognition.

The game’s conception came from Jeff Cretcher, who served as co-designer and was responsible for directing the filming. The production process involved recording actors in costume in an empty studio, with the scenery later being digitally composited from photographs taken at real locations in Greece. This methodology allowed the team to create a relatively impressive visual presentation for the standards of the time, even with limited resources. Marty Beckers later worked on updating the program for compatibility with more modern computers, ensuring that the game’s script matched the playable experience exactly.

The script used during filming served simultaneously as a guide for video production and for programming the game itself. This document was later expanded with additional information available through the game’s information system, transforming into an educational resource that players could consult during the adventure. Luminaria marketed the product both as a game and as an educational tool, including warnings to more experienced players that the material contained hints about the challenges.

The narrative of Wrath of the Gods begins with a cinematic prologue set in the stormy heights of Mount Olympus, presenting the mythological context through narration about the Greek Heroic Age. The player assumes the role of an unnamed hero, grandson of the king of Mycenae, whose life is marked by the prophecy of the Oracle of Delphi that he would one day rule in place of his grandfather. Fearing this prediction, the king orders the baby to be abandoned on a deserted mountain, where he is found and raised by Chiron, the wise centaur known for educating heroes.

The protagonist’s journey begins when Chiron declares that he has completed his education, giving him a ring that was in his blanket when he was found, along with some gems. The centaur instructs the young hero to venture into the world, find his true parents, and prove his worth. This premise establishes the narrative structure of the game, which follows the player through multiple encounters based on famous Greek myths, including episodes involving the Hydra of Lerna, Medusa, the Minotaur, the Chimera, and various other mythological monsters and challenges.

The gameplay system of Wrath of the Gods follows the traditional point-and-click graphic adventure model, where the player uses the mouse to interact with objects, characters, and environments. The interface presents different cursors for distinct actions: a hand cursor to pick up items, an eye cursor to examine objects, a speech cursor to talk to characters, and a walking cursor for movement. The inventory appears at the bottom of the screen when activated, allowing the player to combine objects or use them in specific situations.

Progression through the game fundamentally depends on solving puzzles based on logic and mythological knowledge. Many challenges require the player to have obtained specific objects in previous locations, creating a non-linear structure where multiple areas can be explored in different orders. For example, early in the adventure, the player encounters a stone blocking the path. To move it, it is necessary to use the principle of the lever, as Theseus did in his own myth, combining a branch with a smaller stone that serves as a fulcrum.

One of the first significant challenges involves crossing a river, where two women ask the hero for help. This sequence directly adapts the myth of Jason, testing whether the player will choose to help the young and beautiful woman or the old woman with no apparent reward. The correct decision is to carry the old woman, who reveals herself to be Hera in disguise. The goddess then becomes the hero’s patron and promises that the gods of Olympus will accompany his journey, granting divine favor if he succeeds. This choice exemplifies how the game incorporates elements of morality and narrative consequences based on player decisions.

The scoring system in Wrath of the Gods rewards both puzzle solving and completion of action challenges. Major achievements grant 25 or 50 points, with the accumulated total viewable through the help icon. However, unlike many graphic adventures, some challenges can result in penalties if the player uses the Oracle’s help resources, which deduct points in exchange for specific hints on how to proceed.

The death and resurrection mechanic represents an interesting aspect of the game’s design. When the player fails certain challenges or is defeated by enemies, instead of simply restarting from the last save, he is transported to Mount Olympus, where Zeus or other gods comment on the failure. Zeus frequently provides hints about what went wrong, sometimes with sarcastic humor. For example, if the player dies while facing the Hydra without help, Zeus comments on the importance of not attacking alone. If he dies at the Clashing Rocks, the god criticizes the lack of attention to the resources available on the Argo ship.

Navigation through the game requires the character to revisit previous areas with new items or knowledge. The system of dragon-drawn chariot terminals serves as a fast travel mechanism between three main locations: Mycenae, Mount Pelion, and the Hesperides. Within these terminals, the player can purchase tickets for two gems, avoiding long walks. The terminals include environmental details such as flight announcements, slot machines, and departure boards listing fictional destinations beyond the three functional ones, adding depth to the game world.

The resolution of some puzzles demonstrates considerable creativity in design. In the episode of the Sown Men, adapted from the myth of Jason in Colchis, the player plants dragon’s teeth that sprout as armed warriors. Fighting all of them directly is impossible, as they emerge indefinitely. The correct solution involves throwing a stone at one of the warriors, making him believe that another attacked him, resulting in a general brawl that eliminates all enemies. This puzzle rewards knowledge of the original myth and lateral thinking.

The combat system in Wrath of the Gods varies significantly depending on the encounter. Some battles are completely puzzle-based, such as the Hydra or Medusa, where preparation and mythological knowledge determine success. Others incorporate action timing elements, particularly the bull-leaping at the school of Knossos in Crete. In this sequence, the player must click precisely at the right moment to grab the charging bull’s horns and leap over its back, landing safely. Clicking too early results in a jump over empty air; too late means being trampled.

The final fight against the Minotaur in the center of the Labyrinth combines the timing element of bull-leaping with fistfighting. First, the player must avoid the Minotaur’s charge by leaping over it at the precise moment, exactly as practiced at the bull-leaping school. After the successful leap, the confrontation transforms into a hand-to-hand combat sequence where the player must strike the monster repeatedly until defeating it. This final challenge grants 50 points and represents the climax of the main adventure.

Navigation through the Labyrinth itself presents two resolution methods. The player can meticulously map the winding corridors, noting each turn and dead end until finding the center and subsequently the exit. Alternatively, they can use the ball of thread given by Princess Ariadne, which automatically guides through the labyrinth when used from the inventory. This dual implementation allows players with different preferences to approach the challenge in distinct ways, although using the ball of thread is clearly the intended solution within the mythological context.

The hint system through the Oracle of Delphi allows stuck players to receive guidance, albeit at a cost. Some hints are free, particularly for complex puzzles like the labyrinth or underwater navigation after Minos throws his ring into the sea. Others require payment in points, deducting from the accumulated total. The Oracle can also, for a fee, transport the player directly to certain locations, although this results in a point penalty and reduces the satisfaction of exploration.

Exploration of the world reveals attention to historical and architectural details. Ruins of classical structures, roadside shrines, bustling markets, and imposing temples create an atmosphere that evokes ancient Greece. The game’s manual provides extensive educational context about each location, explaining historical significance and cultural details. For example, when encountering a shrine, the manual discusses blood offerings versus bloodless offerings, composition of honey and wheat cakes, and the role of shrines in Greek religiosity.

Slot machines in the terminals are purposely rigged to give the player enough gems for passages. This generous design prevents players from getting stuck without travel resources, recognizing that revisits to locations would be frustrating without fast travel. Occasional announcements echo in the terminal.

The visual presentation of Wrath of the Gods produced a dated aesthetic even for 1994. The actors perform in a broad theatrical style appropriate for epic myths, but technical limitations of video compression result in visual artifacts. Camera movements are virtually nonexistent, with scenes consisting mainly of static framings where characters enter, perform actions, and exit.

Audio quality varies considerably. The recorded dialogue presents inconsistent volume levels and distortions, demonstrating equipment limitations and little care in post-production. The ambient music consists mainly of orchestral synthesizer attempting to represent epic grandeur, but they came out generic. Sound effects range from adequate (ocean waves, footsteps, thunder) to obviously synthetic (inventory sounds, magical transitions).

Some voices sound natural and engaged, while others seem like emotionless script readings. Olympian gods receive more dramatic vocal treatment, with reverb processing added to suggest supernatural power. In the case of less important characters, it’s clear that the actors didn’t fully understand the context of their lines.

Bugs and technical problems plague the experience. Clicks occasionally don’t register correctly, requiring multiple attempts to interact with objects. Some puzzles have imprecise hitboxes where clicking slightly outside the intended area produces no result. Transitions between scenes sometimes present delays while loading as video decompresses. Later versions fixed some problems but introduced others related to compatibility with newer operating systems.

It’s a game to be played through to the end only once. From the moment you solve the puzzles and memorize the paths, there’s no more fun. The only thing that might make someone play again is the fact that there are several side quests that don’t interfere with scoring and aren’t necessary to complete the game.

The critical reception of Wrath of the Gods was mixed. Educational publications praised the attempt to make classical mythology accessible and engaging for students. Game critics were less enthusiastic, citing clunky interface, convoluted puzzles, and inferior technical production compared to contemporary graphic adventures with larger budgets. The rating on MobyGames reflects this division, with scores varying significantly depending on whether reviewers prioritized educational value or entertainment quality.

Inevitable comparisons with Myst (1993) and other CD-ROM graphic adventures of the time highlight the limitations of Wrath of the Gods. While Myst offers high-quality pre-rendered environments and elegant puzzle design, Wrath of the Gods relies on low-resolution real actors and puzzles dependent on specific knowledge rather than deducible logic. The educational game market of the time had different expectations, but conventional players found the experience below established standards.

Sales were modest, with the title never achieving significant market penetration. Distribution focused primarily on educational channels and educational software catalogs rather than mainstream game retailers. This marketing strategy reflected the product’s ambiguous positioning between entertainment and education, not completely satisfying either category.

The educational value remains debatable. While the game exposes authentic mythological narratives and includes substantial contextual information, the integration with the playable portion is superficial. Learning about the myths is useful for solving puzzles, but doesn’t necessarily deepen understanding of the themes, symbolism, or cultural significance of the myths. The game functions more as a test of existing knowledge than an effective teaching tool.

The development team invested significant effort in mythological research, video production, and design, but the problems of technical execution, user interface, and difficulty balance prevent these intentions from fully materializing. The result is a product that fails to transcend its origins as educational software to achieve excellence as a game.

Wrath of the Gods remains as a title from a specific era when CD-ROM technology allowed rich multimedia experiences, exploring the potential of games to teach as well as entertain. Although it didn’t achieve the highest goals in either dimension, the game preserves a unique moment when classical mythology met emerging digital technology.

Wrath of the Gods – O Guia Definitivo

Wrath of the Gods representa um dos títulos mais importantes da produção de jogos educacionais na década de 1990, combinando aventura gráfica point-and-click com uma abordagem sobre mitologia grega, utilizando vídeos digitalizados de atores reais em cenários fotografados na Grécia. Esta fusão de tecnologia FMV (Full Motion Video) com conteúdo didático posicionou o título como uma tentativa ambiciosa de equilibrar entretenimento e aprendizado, embora suas limitações técnicas e de design tenham impedido que alcançasse reconhecimento mais amplo.

A concepção do jogo partiu de Jeff Cretcher, que atuou como co-designer e foi responsável pela direção das filmagens. O processo de produção envolveu a gravação de atores caracterizados em um estúdio vazio, com os cenários sendo posteriormente compostos digitalmente a partir de fotografias tiradas em locações reais na Grécia. Esta metodologia permitiu que a equipe criasse uma apresentação visual relativamente impressionante para os padrões da época, mesmo com recursos limitados. Marty Beckers posteriormente trabalhou na atualização do programa para compatibilidade com computadores mais modernos, garantindo que o script do jogo correspondesse exatamente à experiência jogável.

O roteiro utilizado durante as filmagens serviu simultaneamente como guia para a produção de vídeo e para a programação do jogo em si. Este documento foi posteriormente expandido com informações adicionais disponíveis através do sistema de informações do jogo, transformando-se em um recurso educacional que os jogadores podiam consultar durante a aventura. A Luminaria comercializou o produto tanto como jogo quanto como ferramenta educacional, incluindo avisos aos jogadores mais experientes de que o material continha dicas sobre os desafios.

A narrativa de Wrath of the Gods começa com um prólogo cinematográfico ambientado nas alturas tempestuosas do Monte Olimpo, apresentando o contexto mitológico através de narração sobre a Era Heroica grega. O jogador assume o papel de um herói sem nome, neto do rei de Micenas, cuja vida é marcada pela profecia do Oráculo de Delfos de que um dia governaria no lugar de seu avô. Temendo esta previsão, o rei ordena que o bebê seja abandonado em uma montanha deserta, onde é encontrado e criado por Quíron, o centauro sábio conhecido por educar heróis.

A jornada do protagonista inicia-se quando Quíron declara que completou sua educação, entregando-lhe um anel que estava em seu cobertor quando foi encontrado, além de algumas gemas. O centauro instrui o jovem herói a se aventurar pelo mundo, encontrar seus verdadeiros pais e provar seu valor. Esta premissa estabelece a estrutura narrativa do jogo, que segue o jogador através de múltiplos encontros baseados em mitos gregos famosos, incluindo episódios envolvendo a Hidra de Lerna, Medusa, o Minotauro, a Quimera e diversos outros monstros e desafios mitológicos.

O sistema de jogo de Wrath of the Gods segue o modelo tradicional das aventuras gráficas point-and-click, onde o jogador utiliza o mouse para interagir com objetos, personagens e ambientes. A interface apresenta cursores diferentes para ações distintas: um cursor de mão para pegar itens, um cursor de olho para examinar objetos, um cursor de fala para conversar com personagens e um cursor de caminhada para movimentação. O inventário aparece na parte inferior da tela quando acionado, permitindo que o jogador combine objetos ou os utilize em situações específicas.

A progressão através do jogo depende fundamentalmente da resolução de quebra-cabeças baseados em lógica e conhecimento mitológico. Muitos desafios requerem que o jogador tenha obtido objetos específicos em localizações anteriores, criando uma estrutura não-linear onde múltiplas áreas podem ser exploradas em diferentes ordens. Por exemplo, logo no início da aventura, o jogador encontra uma pedra que bloqueia o caminho. Para movê-la, é necessário utilizar o princípio da alavanca, como Teseu fez em seu próprio mito, combinando um galho com uma pedra menor que serve de ponto de apoio.

Um dos primeiros desafios significativos envolve a travessia de um rio, onde duas mulheres pedem ajuda ao herói. Esta sequência adapta diretamente o mito de Jasão, testando se o jogador escolherá ajudar a mulher jovem e bela ou a anciã sem recompensa aparente. A decisão correta é carregar a mulher idosa, que se revela ser Hera disfarçada. A deusa então se torna patrona do herói e promete que os deuses do Olimpo acompanharão sua jornada, concedendo um favor divino caso ele obtenha sucesso. Esta escolha exemplifica como o jogo incorpora elementos de moralidade e consequências narrativas baseadas nas decisões do jogador.

O sistema de pontuação em Wrath of the Gods recompensa tanto a resolução de quebra-cabeças quanto a conclusão de desafios de ação. As principais conquistas concedem 25 ou 50 pontos, com o total acumulado podendo ser verificado através do ícone de ajuda. No entanto, diferentemente de muitas aventuras gráficas, alguns desafios podem resultar em penalidades caso o jogador utilize recursos de ajuda do Oráculo, que deduz pontos em troca de dicas específicas sobre como proceder.

A mecânica de morte e ressurreição representa um aspecto interessante do design do jogo. Quando o jogador falha em certos desafios ou é derrotado por inimigos, em vez de simplesmente reiniciar do último save, ele é transportado para o Monte Olimpo, onde Zeus ou outros deuses comentam sobre o fracasso. Zeus frequentemente fornece dicas sobre o que deu errado, às vezes com humor sarcástico. Por exemplo, se o jogador morre ao enfrentar a Hidra sem ajuda, Zeus comenta sobre a importância de não atacar sozinho. Se morrer nas Rochas que Se Chocam, o deus critica a falta de atenção aos recursos disponíveis no navio Argo.

A navegação pelo jogo exige que o personagem revisite áreas anteriores com novos itens ou conhecimentos. O sistema de terminais de carruagens puxadas por dragões serve como mecanismo de transporte rápido entre três localizações principais: Micenas, Monte Pélion e Hespérides. Dentro destes terminais, o jogador pode comprar passagens por duas gemas, evitando longas caminhadas. Os terminais incluem detalhes ambientais como anúncios de voos, máquinas caça-níqueis e painéis de partidas listando destinos fictícios além dos três funcionais, adicionando profundidade ao mundo do jogo.

A resolução de alguns quebra-cabeças demonstra criatividade considerável no design. No episódio dos Homens-Semente, adaptado do mito de Jasão em Cólquida, o jogador planta dentes de dragão que brotam como guerreiros armados. Lutar contra todos diretamente é impossível, pois eles surgem indefinidamente. A solução correta envolve arremessar uma pedra em um dos guerreiros, fazendo-o acreditar que outro o atacou, resultando em uma briga generalizada que elimina todos os inimigos. Este puzzle recompensa o conhecimento do mito original e o pensamento lateral.

O sistema de combate em Wrath of the Gods varia significativamente dependendo do encontro. Algumas batalhas são completamente baseadas em quebra-cabeças, como a Hidra ou Medusa, onde a preparação e conhecimento mitológico determinam o sucesso. Outras incorporam elementos de timing de ação, particularmente o salto de touro na escola de Cnossos em Creta. Nesta sequência, o jogador deve clicar precisamente no momento certo para agarrar os chifres do touro em investida e saltar sobre suas costas, pousando com segurança. Clicar muito cedo resulta em um salto sobre o ar vazio; muito tarde significa ser atropelado.

A luta final contra o Minotauro no centro do Labirinto combina o elemento de timing do salto de touro com combate de socos. Primeiro, o jogador deve evitar a investida do Minotauro saltando sobre ele no momento preciso, exatamente como praticado na escola de salto de touro. Após o salto bem-sucedido, o confronto se transforma em uma sequência de combate corpo-a-corpo onde o jogador deve golpear o monstro repetidamente até derrotá-lo. Este desafio final concede 50 pontos e representa o clímax da aventura principal.

A navegação pelo Labirinto em si apresenta dois métodos de resolução. O jogador pode meticulosamente mapear os corredores tortuosos, anotando cada virada e caminho sem saída até encontrar o centro e posteriormente a saída. Alternativamente, pode utilizar o novelo de linha dado pela Princesa Ariadne, que automaticamente guia através do labirinto quando usado do inventário. Esta implementação dupla permite que jogadores com diferentes preferências abordem o desafio de maneiras distintas, embora usar o novelo seja claramente a solução pretendida dentro do contexto mitológico.

O sistema de dicas através do Oráculo de Delfos permite que jogadores emperrados recebam orientação, embora com custo. Algumas dicas são gratuitas, particularmente para quebra-cabeças complexos como o labirinto ou a navegação subaquática após Minos jogar seu anel no mar. Outras exigem pagamento em pontos, deduzindo do total acumulado. O Oráculo também pode, mediante pagamento, transportar o jogador diretamente para certas localizações, embora isso resulte em penalidade de pontos e reduza a satisfação da exploração.

A exploração do mundo revela atenção aos detalhes históricos e arquitetônicos. Ruínas de estruturas clássicas, santuários à beira da estrada, mercados movimentados e templos imponentes criam uma atmosfera que evoca a Grécia antiga. O manual do jogo fornece contexto educacional extensivo sobre cada localização, explicando significados históricos e detalhes culturais. Por exemplo, ao encontrar um santuário, o manual discute oferendas de sangue versus oferendas sem sangue, composição de bolos de mel e trigo, e o papel dos santuários na religiosidade grega.

Caça-níqueis nos terminais estão propositalmente manipulados para dar ao jogador gemas suficientes para passagens. Este design generoso previne que jogadores fiquem presos sem recursos de viagem, reconhecendo que revisitas aos locais seriam frustrantes sem transporte rápido. Anúncios ocasionais ecoam no terminal.

A apresentação visual de Wrath of the Gods produziu uma estética datada mesmo para 1994. Os atores performam em estilo teatral amplo apropriado para mitos épicos, mas limitações técnicas da compressão de vídeo resultam em artefatos visuais. Movimentos de câmera são praticamente inexistentes, com cenas consistindo principalmente de enquadramentos estáticos onde personagens entram, performam ações e saem.

A qualidade de áudio varia consideravelmente. O diálogo gravado apresenta níveis de volme inconsistentes e distorções, demonstrando limitações de equipamento e pouco cuidado na pós-produção. A música ambiente consiste principalmente de sintetizador orquestral tentando representar grandeza épica, mas ficaram genéricas. O efeitos sonoros variam de adequados (ondas do oceano, passos, trovão) a obviamente sintéticos (sons de inventário, transições mágicas).

Algumas vozes parecem naturais e engajadas, enquanto outras parecem leituras de script sem emoção. Deuses olimpianos recebem tratamento vocal mais dramático, com processamento de reverberação adicionado para sugerir poder sobrenatural. No caso de personagens de menor importância, fica claro que os atores não entenderam completamente o contexto de suas falas.

Bugs e problemas técnicos afligem a experiência. Cliques ocasionalmente não registram corretamente, exigindo múltiplas tentativas para interagir com objetos. Alguns puzzles têm hitboxes imprecisas onde clicar ligeiramente fora da área pretendida não produz resultado. Transições entre cenas às vezes apresentam atrasos ao carregar enquanto vídeo decompressa. Versões posteriores corrigiram alguns problemas mas introduziram outros relacionados à compatibilidade com sistemas operacionais mais novos.

É um jogo para ser jogado até o fim apenas uma vez. A partir do momento que você soluciona os quebra-cabeças e memoriza os caminhos, não há mais diversão. A única coisa que pode fazer alguém jogar novamente, é o fato de ter várias missões secundárias que não interferem na pontuação, e não são necessárias para completar o jogo.

A recepção crítica de Wrath of the Gods foi mista. Publicações educacionais elogiaram a tentativa de tornar mitologia clássica acessível e engajante para estudantes. Críticos de jogos foram menos entusiastas, citando interface desajeitada, quebra-cabeças complicados e produção técnica inferior comparada a aventuras gráficas contemporâneas de orçamento maior. A classificação no MobyGames reflete esta divisão, com pontuações variando significativamente dependendo de se revisores priorizavam valor educacional ou qualidade de entretenimento.

Comparações inevitáveis com Myst (1993) e outras aventuras gráficas de CD-ROM da época destacam limitações de Wrath of the Gods. Enquanto Myst oferece ambientes pré-renderizados de alta qualidade e design de quebra-cabeças elegante, Wrath of the Gods confia em atores reais com baixa resolução e puzzles dependentes de conhecimento específico ao invés de lógica dedutível. O mercado de jogos educacionais da época tinha expectativas diferentes, mas jogadores convencionais encontraram experiência aquém de padrões estabelecidos.

As vendas foram modestas, com o título nunca alcançando penetração significativa de mercado. A distribuição focou principalmente em canais educacionais e catálogos de software educativo ao invés de varejistas de jogos do público em geral. Esta estratégia de marketing refletiu posicionamento ambíguo do produto entre entretenimento e educação, não completamente satisfazendo nenhuma categoria.

O valor educacional permanece discutível. Enquanto o jogo expõe narrativas mitológicas autênticas e inclui informações contextuais substanciais, a integração com a parte jogável é superficial. Aprender sobre os mitos é útil para resolver quebra-cabeças, mas não necessariamente aprofundam a compreensão dos temas, simbolismo ou significado cultural dos mitos. O jogo funciona mais como teste de conhecimento existente, que ferramenta de ensino efetiva.

A equipe desenvolvedora investiu esforço significativo em pesquisa mitológica, produção de vídeo e design, mas os problemas de execução técnica, interface de usuário e equilíbrio de dificuldade impedem que essas intenções se concretizem completamente. O resultado é um produto que falha em transcender suas origens como software didático para alcançar excelência como jogo.

Wrath of the Gods permanece como título de uma era específica quando a tecnologia de CD-ROM permitia experiências multimídia ricas, explorando o potencial de jogos para ensinar além de entreter. Embora não tenha alcançado os objetivos mais elevados em nenhuma dimensão, o jogo preserva um momento único, quando a mitologia clássica encontrou a tecnologia digital emergente.